Fighting The Astro-Turfing Of Culture, The Gravity Well Of Banality, And The Stifling Grip Of Pre-Packaged Thinking

“There is certainly another world, but it is in this one”

Paul Éluard

TL;DR

If we’re to resist the gravity well of banality, extract ourselves from of the containers of the past, escape the stifling grip of pre-packaged thinking, refuse to be complicit in the astro-turfing of culture, and create better, desired futures rather than merely slipstream into default ones, then what we really need is imagination. And the recognition that in the quest for transformation, this is the primary working method of strategy.

Caveats and cautions

Given the volume of agency rhetoric about ‘culture’ is matched only by its spectacular vagueness, I feel obliged to to clarify that by ‘culture’ I mean here both the tangible, visible, concrete outputs and expressions of consumer culture, as well as the invisible body of meaning that sits beneath and informs them. More on that here, if you really want it. Given some of the stones I’ll throw at popular culture, I should also clarify that I love watching Below Deck (Captain Lee AND Captain Sandy), Real Housewives (I have watched every episode of RHOBH), Selling Sunset, and Buying Beverly Hills. During lockdown I watched every single episode of Friends. And every single episode of Sex and the City. And every episode of Frasier. There is no sci-fi movie too bad for me not to watch. I believe ABBA are and will forever be the best pop act in the world. I think Avatar is a really good movie. I hate Wes Anderson. My favourite twitter account to follow is @raccoonhourly. Finally, deliberately conflating any and all hint of critical thinking with “cynicism” is an act of intellectual gaslighting and dissent suppression in the service, it usually turns out, of self-interest. If you’re inclined towards such thought police tendencies, please keep moving.

Plus ça change

Before talking about change and the shifting tides of culture, it feels necessary to acknowledge and vaguely sketch out (and certainly not exhaustively) what is NOT new, so as not to fall into the trap of peddling any kind of “X is dead”, “X changes everything” or “these are unprecedented times” narrative (there are quite obviously enough of those around already):

We are by nature what Mark Earls calls a “herd species” whose nature has always been to copy each other. I think here of the hipster who threatened to sue a magazine for using his photo in article about hipsters looking alike, before realising that it wasn’t him. So, so many lols.

Money and impatience have always sought the scalable, ‘good enough’ shortcut. Writing recently for the New York Times, Anna Kodé (2023) points to the estimated 420,000 new rental apartments that were built in 2022 in the United States. As if built for somebody with an aggressive disdain for the imaginative possibilities of Lego, these boxy, mid-rise structures with their encrustations of (often aggressively colourful) panelling, and predictable ground floor craft brewery and coffee shop tenants, they are indistinguishable from one another. Guess the city, Kodé challenges us.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/20/realestate/housing-developments-city-architecture.html

Pop music, movies, genre fiction, TV dramas, blockbuster video games… the culture industries already recycle and reformulate familiar and simple formulae and basic elements, endlessly combining and remixing them in “new enough” ways.

People have long enjoyed the familiar, the derivative, and the undemanding whether as a respite from the daily grind, or from boredom, or to escape from the dread tug of existential angst. If movie posters all look the same, it’s because we really don’t care.

And of course people have always adapted and evolved their habits and behaviours to new tools and technology.

Etc. Etc. Etc.

Plus ça change.

But something else is now afoot. Something that is accelerating and amplifying these natural tendencies and appetites.

Ours is an ever more computational, data-driven, and algorithmically-mediated culture in which anything and everything can (seemingly) be measured, categorised, formularised, copied, iterated, and optimised.

It’s what Neil Postman once called the ‘technopoly’ - “the submission of all forms of cultural life to the sovereignty of technique and technology”(Postman, 1992). This has consequences, even they are not immediately visible to us. As Marshall McLuhan understood, culture is ultimately shaped by the technological evolution of media even though this may be invisible to us. As he said in his famous Playboy (1969) interview:

“Man remains as unaware of the psychic and social effects of his new technology as a fish of the water it swims in. As a result, precisely at the point where a new media-induced environment becomes all pervasive and transmogrifies our sensory balance, it also becomes invisible”

The consequence is that in both its practical workings and in its general orientation, values, aspirations, and behaviours, culture is beginning to look, to borrow the words of Derek Thompson writing for The Atlantic, like “a solved equation”.

One in which anything is endlessly open to categorisation, standardisation, replication, measurement, iteration, and optimisation.

This is not an entirely new phenomenon. The turn away from imagination and towards empiricism has long been underway. The will to analyse experience, to identify and exploit the immutable laws of how the world works, to break things down into manageable and understandable parts, the prioritisation of explicit knowledge over tacit, the hunger for ‘objective’ and ‘measurable’ results began of course in the Enlightenment - the knowledge revolution of the early seventeenth century - and was (quite literally industrialised) in the Industrial Revolution. Ripple dissolve, and we now find ourselves in a culture that as the cultural critic Henry Giroux (2016) has argued, is drowning, “in a new love affair with empiricism and data collecting” and that dismisses or marginalises imagination. In his book Lost Knowledge of the Imagination, the writer (and former bassist for Blondie) Gary Lachman cautions us against simply accepting received wisdom:

“We say it is 'just imagination' because we have been taught to do so. If we are more familiar with the quantitative way of knowing, that is because we are taught that this is knowing, and that anything else is wishful thinking and make believe.”

It’s a cultural tilt that risks forgetting that science is not the only way of knowing our world. As the American physicist, astronomer, and writer Adam Frank (2021) has argued:

“There can be no experience of the world without the experiencer and that, my dear friends, is us. Before anyone can make theories or get data or have ideas about the world, there must be the raw presence of being-in-the-world. The world doesn’t appear in the abstract to a disembodied perspective floating in space… it appears to us, exactly where and when we are. That means to you or to me right now. In other words, you can’t ignore the brute, existential, phenomenological fact of being subjects… The problem with the God’s-eye view of science is that it confuses the illusion of being right for actually being in accord with the weirdness of being an experiencing subject. It appears to offer a perfect, hermetically sealed account of the universe that seems so beautiful until you realize it’s missing the most important quality: life. Not life as an account of a thermodynamic system, but life as our embodied, lived experience.”

Temperature, blood pressure, blood oxygen, heart rate, breathing rate, steps, floors climbed, distance traveled, calories burned, active minutes, sleep time, sleep quantity, biphasic shift, basal body temperature… Instead of embodied knowledge and insight, we are able to subcontract the work to our smarter, more objective, more dependable devices. Thanks to them our bodies are now trackable, hackable entities capable of being understood as data points we can optimise. “Self-knowledge through numbers” in the words of the Quantified Self website.

This cultural recalibration towards the veneration of the Trinity of the Science, the Data, and the Holy Model is arguably all but fully complete in the domain of business. My favourite business thinker and management consultant (and hardly a creative or adland luvvie) Roger Martin has argued (2022), that it is a world that has been fully captured by science- and analysis-obsessed technocrats who “[favour] analysis of the known over any other kind of thought or work”.

The sonic boom of this cultural shift now courses across the educational landscape. Consider for example, that in the US, the number of college students graduating with a humanities major has fallen for the eighth straight year to under 200,000 degrees in 2020. Or put another way, that fewer than one in ten college graduates obtained humanities degrees in 2020 - down 25 percent since 2012. In sharp contrast, since 2008 the number of STEM majors in bachelor’s degree-and-above programs has increased 43% from 388,000 graduates in 2009-10 to 550,000 in 2015-16 (EMSI, 2016).

At the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, new undergraduate courses launched within the last two years include: Intro to Analytics and the Digital Economy, Data Science for Finance, AI, Data, and Society, Data Mining for Business Intelligence, Modern Data Mining, Predictive Analytics Using Financial Disclosures, Health Care Data and Analytics, and Marketing Analytics. Columbia Business School's new offerings include: Healthcare Analytics, The Analytics Advantage, Artificial Intelligence Strategy, Data Science for Marketing Managers, and Real Estate Analytics.

In the UK the so-called Browne Report of 2010 on the funding of higher education (‘Securing a sustainable future for higher education’) had indicated the future direction of travel stating that “a degree is of benefit both to the holder, through higher levels of social contribution and higher lifetime earnings, and to the nation, through higher economic growth rates and the improved health of society”.

The UK Sheffield Hallam University dropped its English Literature course from this year, citing “a lack of demand” and that its graduates “struggle to get highly paid jobs”. Similarly, Roehampton University confirmed last year that it would firing and re-hiring half its academic staff and focusing on new “career-focussed courses” across all departments.

The recent handwringing over the likely consequences of LLM/AI ignores the fact that as the American writer, editor, and teacher of writing John Warner has argued, a rule-bound education system means that we’re already teaching kids to write like ChatGPT. The teaching of writing skills in the US has become he argues, the pursuit of “proficiency” or “competency,” in which students are given rules and strictures within which to think. Or at least write. The writing doesn’t need to be accurate or well argued, and it definitely doesn’t need to be interesting, let alone original. Instead students are coached to something that seems like it could be accurate or well argued and pass muster on a test. It’s about “privileging surface-level correctness” rather than rhetorical, writing, and critical thinking skills (Warner 2018). It’s not knowing how to think, but how to please the model.

Never mind that famed aphorism (misattributed to Peter Drucker) about “culture eating strategy for breakfast” - the algorithm is now eating culture for breakfast.

Look what’s happening…

It’s a culture in which the algorithm itself is now our first audience.

Ian Lesliew, hose recent writings provided so much of the inspiration and impetus for journey down this rabbit hole, describes (2022) how the creation of music is shapeshifting:

Spotify uses machine learning to identify what kinds of songs are successful at winning user attention at the moment, then they push songs which conform the model to the top of the queue by adding them to playlists. The result is a penalty for complexity, variation and surprise - for anything the algorithm may not recognise. A feedback loop ensues, as musicians respond by creating songs to fit the model, and everyone herds towards the latest trend.

For example, to qualify as having been listened to on Spotify, a song has to have been played for thirty seconds, with the consequence that hit songs have become increasingly predictable, as artists cut out introduction sections to deliver the most catchy bits in the opening half-minute, and simplifying choruses.

And the music is not just become more simple, it’s becoming shorter. Because only the first 30 seconds are necessary for the stream count, the rest of the song loses importance. Data scientists from UCLA have tracked the reduction in song lengths back to 1990 – average duration four minutes and 19 seconds – using information taken from a 160K Spotify tracks dataset. They report that from 1930 to 1990 “there was a steady increase in mean song duration (3 minutes 15 seconds to 4 minutes 19 seconds),” and that in 2020, lengths of new releases on Spotify came in at 3 minutes and 17 seconds. Pop song analysts Hit Songs Deconstructed have also shown that in the first three quarters of 2021, 37 per cent of all USA Hot 100 Top 10 hits came in at less than three minutes.

It’s a culture in which data analytics is squeezing out variation.

According to Derek Thompson (2022), the data analytics revolution that we’ve come to know as ‘Moneyball’ has rendered baseball a lot more boring than it used to be. Armed with data analytics and in search of strikeouts, managers have increased the number of pitchers per game and increased the average speed and spin rate per pitcher. In turn, hitters have responded by increasing the starting angles of their swings, increasing the odds of hitting a home run but also making strikeouts more likely.

The consequence has been that whereas in the 1990s, there were typically 50 percent more hits than strikeouts in any game, today there are consistently more strikeouts than hits. In fact there have been more strikeouts per game in the last ten years than in the last hundred and fifth years of major league baseball history. Data, argues Thompson (2022), has solved the ‘equation’ of baseball, and in the process has rendered the game boring:

“Cultural moneyballism, in this light sacrifices exuberance in favour of formulaic symmetry.”

Married to the impatience of capital, creating for the algorithm and the data point is breeding a culture in which versioning is squeezing out originality.

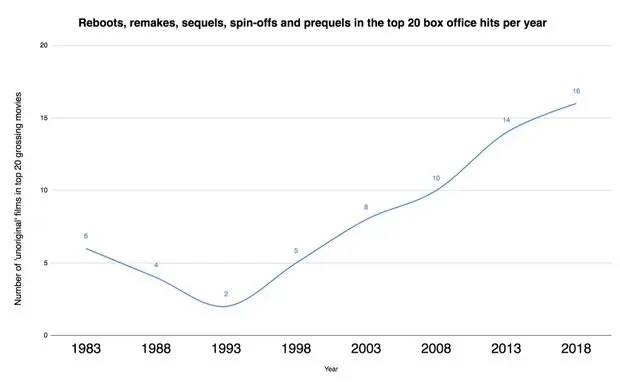

The cultural instalment plan that so far comprises Captain America: The First Avenger, Captain Marvel, Iron Man, Iron Man 2, The Incredible Hulk, Thor, The Avengers, Thor: The Dark World, Iron Man 3, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Guardians of the Galaxy, Guardians of the Galaxy 2, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Ant-Man, Captain America: Civil War, Black Widow, Spider-Man: Homecoming, Black Panther, Doctor Strange, Thor: Ragnarok, Ant-Man and the Wasp, Avengers: Infinity War, Avengers: Endgame, Spider-Man: Far From Home, Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, Eternals, Spider-Man: No Way Home, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, Thor: Love and Thunder, and Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania is no aberration or outlier. Neither is The Fast And The Furious, 2 Fast 2 Furious, The Fast And The Furious, Fast & Furious, Fast Five, Fast & Furious 6, The Fast And The Furious: Tokyo Drift, Furious 7, The Fate Of The Furious, Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, and F9. Looking back at the top 20 grossing films each year going back to the 1980s one finds that the share of them that are sequels, prequels, and reboots has grown sharply:

And in 2019, the top 10 films at the domestic box office included two Marvel sequels, two animated film sequels, a reboot of a ‘90s blockbuster, and a Batman spinoff. And that in 2022, the top 10 films at the domestic box office included… two Marvel sequels, one animated film sequel, a reboot of a 90s blockbuster, and a Batman spinoff. Derek Thompson again:

“Blockbusters are kind of boring now, not because Hollywood is stupid, but because it’s got so smart”.

Look at how swathes of contemporary art actively embrace industrial-scale versioning and try to kid us that some sixty years after the Pop Art movement happened it’s an original, witty, and oh-so ironic commentary on consumerism.

Or consider how impossible, as Jaron Lanier challenges us, to point to any music that is characteristic of the late 2000s as opposed to the late 1990s.

The music journalist, former Melody Maker writer, and author Simon Reynolds points to what he sees as the “deficit in newness” across the spectrum, from the fringes to the money-pumping heart of the mainstream. For Reynolds the problem isn’t just the failure of new movements and mega-genres to emerge, or the sluggishness of the established ones, but as he puts it, “the way that recycling and recursion became structural features of the music scene, substituting novelty (difference from what immediately preceded) for genuine innovation. It seemed like everything that ever was got its chance to come back into circulation at some point during the 2000s.” Reynolds cites Pitchfork’s excoriating review of Greta Van Fleet’s debut album Anthem of the Peaceful Army:

“Though their debut album, Anthem of the Peaceful Army, sounds like a bona fide classic rock record—with its fuzzy bass, electric sitar solos, and lyrics featuring the kind of self-actualized transcendence brought on by a few too many multivitamins—it is not actually classic rock. They are a new kind of vampiric band who’s there to catch the runoff of original classic rock using streaming services’ data-driven business model. Greta Van Fleet exist to be swallowed into the algorithm’s churn and rack up plays, of which they already have hundreds of millions. They make music that sounds exactly like Led Zeppelin and demand very little other than forgetting how good Led Zeppelin often were… But for as retro as Anthem of the Peaceful Army may seem, in actuality, it is the future. It’s proof of concept that in the streaming and algorithm economy, a band doesn’t need to really capture the past, it just needs to come close enough so that a computer can assign it to its definite article. The more unique it sounds, the less chance it has to be placed alongside what you already love. So when the Greta Van Fleet of your favourite artist finally lands on your morning playlist, spark up a bowl of nostalgia and enjoy the self-satisfied buzz of recognizing something you already know. It’s the cheapest high in music.”

LLM/ML/AI is likely to turbocharge a culture of variation not origination.

The contemporary art critic and author of Art in the After-Culture Ben Davis contends that:

“The promise of AI is to speed up this process dramatically… no body of work that brings you pleasure need ever be considered a finite resource. If you want a new song that sounds like the Beatles or a new paining that looks like a Basquiat, these are ultimately trivial problems to solve”.

This is surely right up capitalism’s Strasse. After all, as Davis puts it:

“It’s a bit silly to say that AI ‘will never make real culture’ when all the resources of the capitalist ‘culture industry’ are focused exactly on the creative operation that AI does best: analysing what is already known to be popular, then slightly varying its pattern - sometimes very, very slightly - to create a marketable new version of the same”.

But it’s not just the outputs of culture that are changing, but we ourselves.

We are adapting our behaviours and language to what works for the algorithm. As Ed Finn author of What Algorithms Want has talked about how “We shape ourselves around the cultural reality of code, shoring up the facade of computation where it falls short and working feverishly to extend it, to complete the edifice of the ubiquitous algorithm.”

Consider how we adjust our speech patterns to (we hope) make our statements easier for the customer service machines to understand. Or how we plan our weekend activities or summer holiday plans or restaurant choices for optimal self opportunities.

Or consider how in order to communicate via text messages, our communication is forced to become as Alan Kirby , author of Digimodernism puts it:

“Heavy on sledgehammer commands and brusque interrogatives, favoring simple, direct main clauses expressive mostly of sudden moods and needs, incapable of sustained description or nuanced opinion or any higher expression. Restricted mostly to the level of pure emotion (greetings, wishes, laments, etc.) and to the modes of declaration and interrogation, it reduces human interaction to the kinds available to a three-year-old child. Out go subclauses, irony, paragraphs, punctuation, suspense, all linguistic effects and devices; this is a utilitarian, mechanical verbal form."

Or consider how - when we actually do come across them - with their pre-formatted scripts the humans operating customer services now sound like bots.

It used to be that data was formatted to be machine-readable. Today we are reformatting ourselves become machine-readable humans. Consider how as we come to define ourselves more and more through our relationship with the machines, we’ve become content engines for whom process and volume trumps content. Writing for The New Yorker, Kyle Chayka argues that since so much audience attention is funnelled through social media, and the most direct path to success is to cultivate a large digital following this in turn necessitates producing a constant stream of content with which to feed the algorithmic beast upon whom they rely. The consequence he argues is that ‘cultural producers’ who, in the past, would have spent their time and energies on writing books or producing films or making art must now also spend time producing ancillary content about themselves, their lives, their daily routines, the process of their craft or art, the backstory of their cultural production, and their work. All to fill, what Chayka calls “an endless void.”

Consider too, Maria Popova’s Marginalia (formally known as BrainPickings). As Ed Finn argues, it is celebrated primarily for her consistent, timely production of content:

“Its status as a persistent stream of content, one that Popova “obsessively” maintains, makes the stream more valuable than the individual works she cites. The performance of her creative process, the complex human-computational culture machine that is Brain Pickings, becomes the object of interest for her readers”.

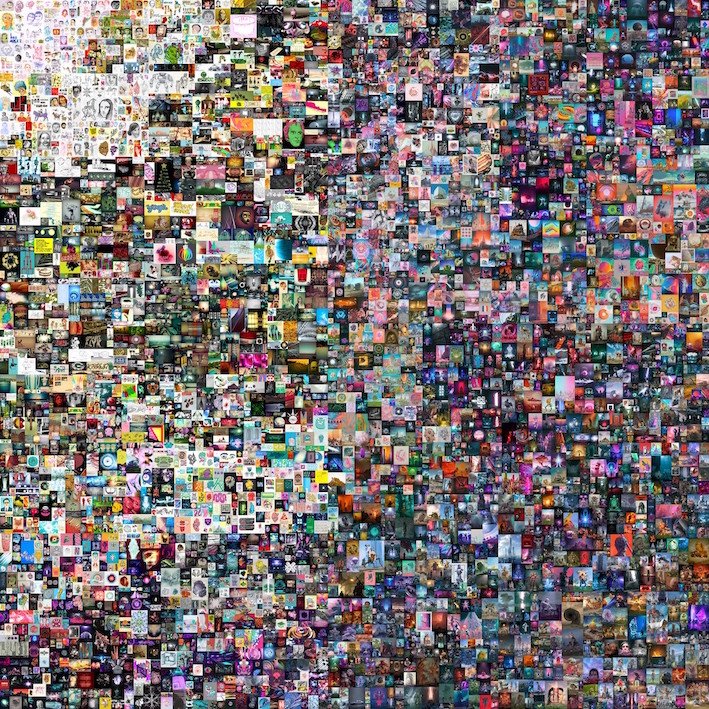

Or consider that the most famous artist in the NFT space, Beeple, had his fame grow out of his “Everydays” project of posting a new piece of artwork every day. Never mind the quality, behold the quantity.

And so, as art Ben Davis writes:

“The effect of the NFT-ization of art feels more like an intensification of the demands on creative life in the age of social media and the tyranny of feeding the algorithm, not a more wholesome, up-with-people alternative to it. Art has been traditionally associated with contemplation. Art in this space is going to be associated with being always-on, always hustling.”

Or consider Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing platform. It enables writers to bypass the traditional gatekeepers of commissioning editors and publishing houses and self-publish their work for free (with Amazon obviously taking a health percentage of the sales revenue). So far so good. But authors are paid by the number of pages that are read - which Parul Sehgal writing for The New Yorker suggests creates a powerful incentive for locating cliffhangers early on in narratives (not just at the end as is traditional), and for generating as many pages as possible, as quickly as possible. Of course the serialised novel with cliffhangers is nothing new. But the demands of algorithm, places pressure on writers to produce not just one book or even a series of books, but a “series of series.” Which Seghal characterises as “something closer to a feed”. Professors Dionysios Demetis & Allen Lee put it even more starkly: “Humans can now be considered artefacts shaped and used by the (system of) technology rather than vice versa”.

Yes, of course good, and even great, stuff still gets made.

We can point to all the edges cases and examples we want. But Sturgeon’s Law is inescapable and as ever, it’s the exceptions that prove the rule.

The consequence of all this ours is that culture in which ambiguity, play, quirk, weirdness, and humanity is being squeezed out.

Consider how franchises and IP have consumed the movie star. As Wesley Morris has argued:

“There are fewer movies, and even fewer of the kind that once allowed an actor to develop a persona over time, to turn into a Tom Cruise: movies about people in jams, in danger, in panic, in pursuit, in heaven, in heat, in Eastwick and Encino and Harlem and Miami, in badlands, lowlands, heartlands, wastelands. Blockbusters, bombs and sleepers. They were relatively inexpensive — middlebrow was one name for them — and they told stories about original characters, not mutations of intellectual property (not always, anyway). And many of the people in them were what we call stars. Folks who were all a little more something than the rest of us — grittier, wittier, prettier, sillier, fitter, wilder, braver, funnier, franker, tougher, loonier, louder.”

Franchises come packed with stars of course, but the stars are no longer characters in their own right. Argues Morris:

"The real stars now are intellectual property — remakes and reboots and cinematic installment plans. Thor, not Chris Hemsworth. Spider-Man as opposed to Tom Holland or Andrew Garfield or Tobey Maguire. All those Batmen…”

One wonders whether this (partially) explains why so many of us loved Top Gun 2 so much and helped make it Tom Cruise’s first billion dollar movie.

Consider too, the colonisation of corporate logos by san serif, the glass-smooth, interest-evading B-21 stealth bomber of fonts.

It represents the triumph of UX design (which favours frictionless simplicity) and graphic design (which favours well, pretty much everything else). Balenciaga, Saint Laurent, Berluti, Balmain, Rimowa… their optimised for screen identities are so infinitely frictionless that they practically bounce off our retinas. This is what the astroturfing of culture looks like. And we ain’t seen nothing yet.

Source: https://www.cheerfulegg.com/2022/12/03/why-does-everything-look-the-same/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=why-does-everything-look-the-same

The machines are going to take over and super-scale the manufacture of the generic.

But we’re likely to see not merely the takeover of generic content production by machines, but a web utterly flooded with an endless and relentless supply, of the derivative and the banal. Never ending “How To..”#threads from billionaire bois, inspirational posts from the shock troops of the wellness movement, Surrey rage posters, strategy “tips” from strat gurus who’ve authored no work you’ve heard of or seen, LinkedIn humblebrags, always-on corporate verbal diarrhea… The wasting our time for the benefit of others seems likely to reach the event horizon beyond which is is impossible to be more exploitative and more devaluing of our attention.

In 2019 Yancey Strickler, author of This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World, and the cofounder of Kickstarter posited what he termed ‘the dark forest theory of the web’. The metaphor borrows from Liu Cixin’s sci-fi trilogy The Three Body Problem. In it Cixin asks us to think differently about the apparent lack of life in the universe (what’s known as Fermi’s Paradox). The universe is like a dark, deathly quiet forest at night, he suggests. One might assume that the forest is devoid of life. But of course, it’s not. The dark forest is full of life. It’s only quiet because night is when the predators come out. And for Strickler, this is what the internet is becoming: a dark forest: “In response to the ads, the tracking, the trolling, the hype, and other predatory behaviors, we’re retreating to our dark forests of the internet, and away from the mainstream." Where will we go when Large Language Models (LLMs) enter the space and industrialise the generation of human-like banality?

Sidenote: There is an upside to this.

Lest this be misconstrued as the cynicism (critical thinking is not, as some would have it, the same as cynicism) of a Luddite, it is worth pointing out the upside. Namely there will a premium for being really, really human. And for being a really, really talented and original human. The poet, computer scientist, and philosophy Brian Christian exhorts us in his book The Most Human Human that in the face of technology becoming ever better at imitating us, we should resist imitating the machines and work to raise our (most human) game:

“For everyone out there fighting to write idiosyncratic, high-entropy, unpredictable, unruly text, swimming upstream of spell-check and predictive auto-completion: Don’t let them banalize you.”

But in the meantime, here comes the endless feed of precision-engineered, algorithm-serving, data-perfected, market-optimised, template-conforming, best-practice leveraging, just different-enough content. Perhaps the music critic, political and cultural theorist Mark Fisher had it right all along:

“Perhaps the feeling most characteristic of our current moment is a mixture of boredom and compulsion. Even though we recognise that they are boring, we nevertheless feel compelled to do yet another Facebook quiz, to read yet another Buzzfeed list, to click on some celebrity gossip about someone we don’t even remotely care about. We endlessly move among the boring, but our nervous systems are so overstimulated that we never have the luxury of feeling bored. No one is bored, everything is boring.”

Marketing is not immune.

While our rhetoric as an industry suggests that we somehow operate outside culture, striving to shape it, change it, or become a part of it, it’s a perspective that is, frankly, bullshit. One cannot be outside culture any more than a goldfish can be out of water. So it’s no surprise that much of these patterns and shifts are already very familiar to those of us in marketing. We’ve long valued process over outcomes, treated people as IT artefacts whose purpose is to process and retain information, outsourced independent, critical thinking and replaced it with The Model, and recycled unproven rules and inherited wisdom. We’re already iterating genre tropes and marginal variations whilst telling ourselves we’re doing something new and different, making things that fit and please the model, trading intensity for volume, and treating the algorithm as our first audience.

We’re already editing out humanity and play.

Peter Field has observed that “Instead of emotionally engaging human stories that seek to charm and captivate, we are seeing more didactic, literal presentations that seek to prompt us into action”. This finds echo in an analysis of 620 ads appearing in Coronation Street between 2004 and 2018 that highlights a significant shift in the style of advertising we are exposed to. Specifically, the analysis reveals a decline in the use of characters, sense of context, distinctive accents, ambiguity, wordplay, double meaning, and metaphor. According to the report’s author Orlando Wood, advertising today demonstrates less self-awareness, is less self-referential, employs less implicit communication between people, deploys less cultural references, and fewer stories with a beginning, a middle and an end. Conversely, it reveals a greater use of voiceovers, monologue, more focus on things than people, more people as props not characters.

The shift is significant, for this is advertising designed for the left-hemisphere. It’s advertising designed for that part of the brain that as Wood characterises it, prizes utility, power and control, whose principle tool is language, that is concerned with cause and effect, that likes clarity and certainty, that is literal and prefers the literal over the implicit. All the things which our culture so enamoured with data, empiricism, science, and logic prizes so much.

This is advertising that neglects the right hemisphere of the brain. This is the part of the brain which understands the world through connections and relationships between things (rather than cause and effect), that’s rooted in bodily or visceral experience, that’s empathetic, understands the feelings of others, and understands what’s implied. It’s the part of the brain that understands metaphor, humour, and irony.

In other words, we are creating more and more advertising which neglects that part of the brain we must engage if we want to create the associations and connections that lie at the heart of long-term brand building. It means that we are giving up on advertising that seeks to influence behaviour not simply through the conscious processing of verbal or factual messages, but as Paul Feldwick characterises it, “by influencing emotions and mediating 'relationships' between the consumer and the brand”.

It’s almost as if people don’t find the vast majority of brands eminently and easily substitutable, as if for all the earnest parroting of “building memory structures” nobody’s thought about attention as the prerequisite for memory, and as if attention has not become a zero-sum game.

Again, it’s important to recognise that good (and really great) stuff does get made.

But are not immune from Sturgeon’s Law and we deny our tendencies at our own risk.

The fact is that we need (to borrow the words of Julian Cope) more switched-on, forward-thinking motherfuckers.

Strategy may well be our greatest defence against banality, our best chance for escaping the containers of the past, and our surest means of slipping from stifling grip of computational culture. For the simple reason that it is concerned about people, and looks to the future. But to realise its potential, strategy needs to be reorientated and reimagined.

When asked to define their role, strategists/planners talk about understanding the consumer, unearthing insights, or sparking opportunities for creativity. But this isn’t strategy. Small wonder that Paul Feldwick was moved to write: “The clients don’t know what it is, we don’t know what it is”.

The fact is that strategy is not just an enabling process or stage that precedes ‘creativity’. It isn’t merely creativity's midwife, fluffer, or springboard.

Nor does strategy merely dedicate itself to understanding the Present. It’s not just pipeline of research and insight about the world today. It’s a way of thinking ourselves out of the constraints and the conditions of the Present and working out how to make a different Future real. One we desire, one that is on our terms, rather than one we simply default to.

In other words, strategy is the opposite of thinking and creating within rules, templates, formats, of recycling and remixing the past, of just tweaking, iterating, and optimising the machinery that’s running today, of copying and pasting best practice and telling ourselves we’re doing something different.

To that end…

As experts in people, we must resist real, useful, empathic and clear-sighted consumer understanding being reduced to the lossy compression we call ‘insight’.

After all, “Young people want to stand out, but as part of the crowd” is still (no, really!) considered by some to be not merely a powerful revelation about the human psyche but useful to the creative process. The fact is that the harder we try to please the self-styled Insight Police (“it must be in the voice of the consumer/it must be one sentence/it must evoke an ah-ha…”) the more we squeeze out the quirk, contradictions, complexity, nuances, and truth that actually make us human. And are the fuel for stuff that is born from a place of genuine empathy - and is not merely relevant, but actually interesting.

As experts in how people consume, make sense of, and use communications, we have to (finally) let go of the silly assumption that people are data processors.

Writing in Frontiers in Computer Science (2022) Blake A. Richards of the School of Computer Science and the Montreal Neurological Institute at McGill University and Timothy P. Lillicrap, neuroscientist and AI researcher, adjunct professor at University College London, and staff research scientist at Google DeepMind, are enormously clarifying and helpful on this. Brains they remind us, do not use sequential processing (quite the opposite they use massively parallel processing), they do not use discrete symbols stored in memory registers (they operate on high-dimensional, distributed representations stored via complex and incompletely understood biophysical dynamics), and they do not passively process inputs to generate outputs using a step-by-step program (they control an embodied, active agent that is continuously interacting with and modulating the very systems that generate the sensory data they receive in order to achieve certain goals). People are not computers. I hope that clears up that silly misconception.

As brand builders, engineers of future demand, and experts in how communications works, we must jettison the inherited and persistent notion that communication is ipso facto synonymous with message transmission and processing.

The linguist and author Guy Deutscher argues in The Unfolding of Language, that one of the features of language is the constant the pull of eloquence and push of efficiency. Made expressly for efficiency, automation is naturally made for - and is likely to encourage - small discourse, low entropy, compressed messaging. In The Most Human Human, Brian Christian cites the Professor of Computer Science at University of New Mexico Dave Ackley saying “if you make discourse small enough, then the difference between faking it and making it starts to disappear”. The fact is that we won’t need humans to produce finely-tuned, timely, responsive, adaptive, small discourse, low entropy, compressed messaging.

And perhaps precisely because of this, we will have to make the case for eloquence not just efficiency, for aesthetics and signals not just language and messages, for the implicit not just the explicit. Because these are the means as Paul Feldwick has argued for “influencing emotions and mediating 'relationships' between the consumer and the brand” that is central to creating long term value.

But don’t believe me, believe the marketing science boffins at The Ehrenberg-Bass Institute. In 2015 they published a paper entitled ‘Creative that Sells: How Advertising Execution Affects Sales’. Their research correlated the short-term sales effectiveness of 312 ads (across five markets) with 89 creative devices, from humour on the one hand to hard sell on the other. Their conclusion was that:

"How advertisers choose to communicate (framing, characters, situations) is possibly more impactful than what is communicated (news, features or benefits).”

As purveyors of enduring solutions (and value), we need to make the case for system-solving intensity and big ideas not just low intensity fractional content that solves the smaller issues.

Back in 1986, Stephen King wrote about what he believed made for a good advertising idea:

“A good advertising idea has to be original enough to stimulate people and draw an intense response from them... Any advertisement is competing not just with other advertisements but also with editorial, programmes, people, events and life itself... if an advertisement is to succeed it has to involve the receiver and entice him into participating actively in whatever is being communicated about the brand”.

Today, however, this is typical of the direction of travel for many CMOs: “Our biggest challenge today is delivering tailored messages to our consumers 24 hours a day, 365 days a year across an increasingly complex communications landscape.”

Finn Brunton, Professor of Science and Technology Studies and Cinema and Digital Media at the University of Aberdeen in his book Spam: A Shadow History of the Internet, defines spam thus:

"Spam is not a force of nature but the product of particular populations distributed through all the world’s countries: programmers, con artists, cops, lawyers, bots and their botmasters, scientists, pill merchants, social media entrepreneurs, marketers, hackers, identity thieves, sysadmins, victims, pornographers, do-it-yourself vigilantes, government officials, and stock touts…. Spammers find places where the open and exploratory infrastructure of the network hosts gatherings of humans, however indirectly, and where their attention is pooled.”

If as Brunton argues: “Spam is the difference - the shear - between what we as humans are capable of evaluating and giving our attention, and the volume of material our machines are capable of generating and distributing when taken to their functional extremes”, then one would be forgiven for concluding that much of marketing already seems to be striving towards the condition and status of spam. Surely the relentless ratcheting up the volume of marketing content (however targeted, timely, and relevant it might be) at both an individual and aggregate level should prompt at least pause for reflection. For as Brunton reminds us:

“The use [spammers] make of this attention is exploitative not because they extract some value from it but because in doing so they devalue it for everyone else - that is, in plain language, they waste our time for their benefit.”

Of course timely, targeted, tailored, context-sensitive, platform adaptive content and messaging has a role in the marketing communications stack. But privileging quantity over intense responses, messages with a half life less than that of beer foam over long and deep ideas, relevance and timeliness over the capturing of imaginations, always having nothing to say over sometimes actually having something to say is not the path to creating the empires of the mind we know as brands. The content engines are going to get supercharged like never before, and the case for ideas and intensity will not make itself.

But there is more we can and must do.

We must rebel against the tyranny of what he writer and educator Brad Carter “the assumption stack”.

As he explains:

“An assumption is something we take to be true without having proof that it is so. This is not to say it’s necessarily wrong, just that it is something we take as a given. All that matters here is that we are aware when we are making assumptions…. An assumption stack is different from a single assumption or even a collection of assumptions in the way the elements of the stack are mutually reinforcing. An assumption stack is a group of assumptions that together form a large, internally consistent structure.”

If you’re promulgating ideas such as persuasion, generational marketing, literal-minded consumers, the death of TV, and so on (and on) you’re complicit in the maintenance of assumptions stacks that get in the way of real progress and value.

We must free ourselves too from tyranny of the merely viable and the possible.

The theorist, activist and author of Dream: Re-imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy Stephen Duncombe writes about the value of utopian imagination, where he speaks of the "tyranny of the possible," suggesting that our solutions to problems are limited when we think only within the constraints of what we currently accept as reality.:

“The problem we see with holding too tightly to the viable and the possible is that one often becomes tactical in nature - going after solutions to pieces of problems based upon one's own expertise and assumptions -optimizing for what one thinks is most important, and what one can "realistically' do. This is fine for simple or complicated problems (think bicycle or Tesla) but will not work for complex problems that need real work at a dynamic systems level (think rainforest), where breaking apart the problem or operating tactically often leads to negative outcomes. Complex problems require thinking forward, more than solving for the present; imagining a better state and then working toward it. The "tyranny of the possible" only sees today's trends playing out. It assumes that tomorrow will be a version of today.”

Analysis alone is not enough because there is no data about the future.

Data, analysis, and logic can obviously help us uncover and understand what is true today. But it is fraught with risk and hazard. The relentless and myopic pursuit of analytics also gives rise to what Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths in their book Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions term ‘overfitting’. Overfitting is the phenomenon in which we place so much confidence in the God-like omniscience and infallibility we ascribe to The Data that we overestimate the fit between its rear-view model of the world and the world itself. Christian and Griffiths put it thus:

"Throughout history, religious texts have warned their followers against idolatry: the worshipping of statues, paintings, relics, and other tangible artefacts in lieu of the intangible deities those artefacts represent. The First Commandment, for instance, warns against bowing down to “any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven.” And in the Book of Kings, a bronze snake made at God’s orders becomes an object of worship and incense-burning, instead of God himself. Fundamentally, overfitting is a kind of idolatry of data, a consequence of focusing on what we’ve been able to measure rather than what matters.”

Moreover, as Roger Martin cautions us :

“Focusing on ‘what is true’ is fine if you are confident that the future will be identical to the past. That is the domain of science and its immutable laws — like gravity. However, in the world of business, the future has the capricious habit of being different than the past, often in fully unpredictable ways. As a business, you want to create that future — not let someone else do it to you.”

Businesses and organisations that want to actively create a future for themselves that they desire rather than simply find themselves in a default future, they will need to accommodate themselves to the truth that however much one might wish for it, there no data about the future. Data by its very nature, can only ever be from the past. As the great military theorist Colin Gray repeatedly reminded us, “We do not have, and will never obtain, evidence from the future about the future.” Analysis can tell us about where we are but it does not as Martin argues, produce great strategy.

In limiting our field of view and preventing us from seeing beyond the borders of the data, overfitting and the rear-view gaze render strategy - which I hope to show is at heart is a free-ranging, imaginative practice - constipated.

At this point one might be expected to turn towards the importance of that thing we call ‘creativity’. Well, not so fast.

Because the fact is that while it wasn’t always thus, when we talk about ‘creativity’ today, what we really mean is the production of things. Amazon for example, is filled to the brim with titles such as: Conscious Creativity: Look. Connect; Create: Managing Change, Creativity and Innovation, Creative Thinking: Practical strategies to boost ideas, productivity and flow, etc. And all that’s fine. Marketing and communication can only ever come into being and be experienced by people through the making of things.

But if we’re to resist the gravity well of banality, extract ourselves from of the containers of the past, escape the stifling grip of computational culture, and refuse to be complicit in the astro-turfing of culture then what we really need is imagination. And arguably, more of it.

We need imagination because while the past can be understood (and repeated, adapted, and iterated) through analysis, the future cannot be analysed. It can only ever be engaged through the imagination - the mental process of speculating beyond probability and what is possible to see what does not exist.

This isn’t mere fluff, and idle pie in the sky fantasising - it’s about exercising agency.

Imagination is not something that just happens in the mind - it’s the trigger for action:

“If we treat the imagination as merely a faculty of the mind, then we will miss the dynamic action-oriented aspect: it is part of the organism’s pragmatic attempt to get maximum grip on its changing environment.”

In fact the professor of history (and author of amongst others, Ideas That Changed the World and Out of Our Minds: What We Think and How We Came to Think It) Felipe Fernández-Armesto goes so far as to argue that: “Imagination… is where most historical change starts… events in the world are commonly the externalisation of ideas”

The fact is that unlike fantasy, imagination is deeply concerned with reality.

Mere fantasising has a healthy disregard for the real world. But imagination works differently, because it actively engages with the world. In the words of Gary Lachman (2017), “imagination is not an escape from reality, not a substitute for it, but a deeper engagement with it.” It begins with the raw materials and dynamics of real world and an understanding of why things are they way they are. But from there it stretches out beyond how things are arranged right now, moving into the unknown, seeing new possibilities, remixing, recombining and rearranging those elements. As the psychologists Caren Walker and Alison Gopnik (2013) observe:

“Conventional wisdom suggests that knowledge and imagination, science and fantasy, are deeply different from one another – even opposites. However, new ideas about children’s causal Causality and Imagination reasoning suggests that exactly the same abilities that allow children to learn so much about the world, reason so powerfully about it, and act to change it, also allow them to imagine alternative worlds that may never exist at all. From this perspective, knowledge about the causal structure of the world is what allows for imagination, and what makes creativity possible. It is because we know something about how events are causally related that we are able to imagine altering those relationships and creating new ones.”

And it is this rearranging of things in the real world that gives imagination the power to change the world in a way that fantasy cannot. Its engagement with the real world allows it to birth not just something new, but something feasible. Something that the world must make space for and accommodate.

So imagining isn’t just about conjuring an image or scene in our mind, with our mind acting as if an impartial and passive observer. In his splendid book William Blake vs. The World, John Higgs sets out to understand how the great English poet, artist and visionary saw the world - and why it looked so profoundly different from how everybody else saw and experienced it. Examining how imagining actually works, he cites the work of the philosopher Edward S. Casey. Casey identified three kinds of imaging - ‘imaging’, ‘imaging-that’, and ‘imaging-how’. Imaging was bringing something to mind. Imaging-that goes beyond that to bring to mind a more complex scene. And imaging-how involves us stepping into that scene (almost as if donning VR goggles) and becoming an active participant in that scene,

To illustrate this, Higgs provides us with an example. If asked to imagine Sherlock Holmes for example, most of us will easily conjure up a mental image - he’s either wearing deerstalker hat, or he’s Benedict Cumberbatch. This is imaging.

We might bring to mind that famous scene of Sherlock Holmes and his nemesis Professor Moriarty struggling above the perilous Reichenbach Falls. This is imaging-that. The scene in the mind is more complex, but we are still observing.

But at its most active - imaging-how - imagination involves placing ourselves in that scene, being an active participant, deciding how to feel, think or act or behave in the scene as it unfurls, working out the details of how it is going to develop in real time, perhaps to rehearse a task or solve a problem or puzzle. So if we’re asked to imagine how as Sherlock Holmes we would escape from Professor Moriarty’s attack above the Reichenbach Falls, we’d imagine say, grabbing onto a tree branch as Moriarty tries to push him over or side-stepping the attack and seeing our nemesis toppling over the falls. This is active, pragmatic, reality-based, problem-solving, knowledge-rearranging imagination at work.

So the fact is that whatever else we’ve been told or inherited, imagination - the ability to see things that do not yet exist, that could exist, or might exist and work out in our minds how they might work - is central to the practice of strategy.

Professor Roger Martin for example, encourages his clients to work backwards from an imagined (attractive) future for the company, and then work backwards asking “What Would Have To Be True” for that to become a reality. Similarly Emeritus Professor of War Studies at King's College London Professor Lawrence Freedman writes: “Strategy starts with an existing state of affairs and only gains meaning by an awareness of how, for better or worse, it could be different.” And Freedman’s words find echo in those of the educational philosopher Maxine Greene:

“To call for imaginative capacity is to work for the ability to look at things as if they could be otherwise… to break with what is supposedly fixed and finished, objectively and independently real.”

They also (unsurprisingly) find echo in Stephen King’s so-called Planning Cycle that he published in 1977, and which asks:

Where are we?

Why are we there?

Where could we be?

How could we get there

Are we getting there?

The key word here is “could”. It’s about possibility, prediction, and imagination.

Professor Martin is clear on what kind of strategic thinking he would place his bet on:

“Somebody who thinks of strategy as involving a lot of imagination, then figuring out how to produce what might be, even though they cannot prove it in advance with analysis, will beat you. They will outflank you.”

Of course we can and should optimise.

As Pendleton-Julian and Brown argue, going after solutions to pieces of problems, and optimizing for what we think we can ‘realistically' do today is fine for relatively simple problems. After all, businesses won’t have a Tomorrow if they don’t have a Today. But optimizing for what we think we can ‘realistically' do today cannot be the only approach. Complex problems require thinking forward, more than solving for the present; imagining a better future state and then working to make it real.

But it is strategic thinking (married to creativity) that is our way out of the gravity well of past, best, and automatic practice.

It’s our way out of finding ourselves in a default future as opposed to a desired one, of doing more than merely iterating and optimising. It’s our path to creating our own rules rather than playing by other people’s and telling ourselves we’re doing the best, right thing. And it’s our bulwark against contributing to the rising tide of banality.

This feels newly urgent.

The challenge today is we are suffering from an imagination deficit. In his book Another World is Possible, Geoff Mulgan Professor of Collective Intelligence, Public Policy and Social Innovation at University College argues that we are experiencing a “closing down” of the imagination”. And in What Should the Left Propose? the Brazilian politician and philosopher Roberto Mangabeira Unger, writes: “The world suffers under a dictatorship of no alternatives. Although ideas all by themselves are powerless to overthrow this dictatorship, we cannot overthrow it without ideas.”

Consider just how difficult it seems to imagine The Future - the idea that the future will be different and better than the present, and how elusive the notion of ‘progress’ seems to be. In After the Future, the Italian communist philosopher, theorist and activist Franco Berardi characterised this phenomenon as the “Slow cancellation of the future [that] got underway in the 1970s and 1980s”. This wasn’t about the mere passing of time, he maintained:

“I am thinking, rather, of the psychological perception, which emerged in the cultural situation of progressive modernity, the cultural expectations that were fabricated during the long period of modern civilisation, reaching a peak after the Second World War. These expectations were shaped in the conceptual frameworks of an ever progressing development.”

That sense (and promise) of development feels less in evidence, despite the incessant hosepipe of novelty we find ourselves on the receiving end of. “The Future, capital-F, be it crystalline city on the hill or radioactive post-nuclear wasteland, is gone”, observed William Gibson (2012), “Ahead of us, there is merely … more stuff … events”. And as the music critic, political and cultural theorist, philosopher Mark Fisher (2014) contended, this “slow cancellation of the future has been accompanied by a deflation of expectations.”

Reporting on their 2023 Annual Global CEO Survey, PWC note that nearly 40% of CEOs think their company will no longer be economically viable a decade from now, if it continues on its current path. The pattern is consistent across a range of economic sectors, including technology (41%), telecommunications (46%), healthcare (42%) and manufacturing (43%).

When asked about the forces most likely to impact their industry’s profitability over the next ten years, about half or more of surveyed CEOs cited changing customer preferences, regulatory change, skills shortages and technology disruption. Roughly 40% flagged the transition to new energy sources and supply chain disruption. And nearly one-third pointed to the potential for new entrants from adjacent industries.

Quite clearly a good many of the world’s business leaders are acutely aware that we’re living in a non-linear world and do not see the trends and dynamics of yesteryear playing out like a straight line into the future. Yet that if one is not careful, is exactly what surrendering to the "tyranny of the possible" and optimising for today falls prey to - the illusion of a Tomorrow that will simply be a version of Today. John Rendon, the former senior communications consultant to the White House and Department of Defense warns us:

“The past as a solution set is not a viable option. We need a new tool set.”

We cannot simply expect the past to be our a solution for tomorrow’s problems. We need, as the architect and former professor at MIT Ann Pendleton-Jullian has argued so passionately, to take imagination more seriously. She writes:

“In a world that is radically contingent, where problems and opportunities are contingent on contexts that are always changing, complex problems are contingent on other complex problems, and opportunities are contingent on other opportunities, we need the imagination: to help us ‘see’ not only what is, but what could be, to help us discover unknown – undiscovered – unknowns to learn new skills and build new capacities to operate in this new era

Despite the increasing need for truly imaginative thinking, we are experiencing a real crisis of imagination. This is due, in part, to a misunderstanding of the role of the imagination and its capacity to problem solve as well as innovate. We are not good at catalyzing it when needed, and more importantly, putting it to pragmatic purpose. The imagination is a muscle that, for many, is wasting away in a world ruled by text, data, pre-packaged images, and “easy” solution-seeking processes”

The implication is clear.

We need more imagination not less of it - and we need more of it as a matter of urgency.

We have to release the brakes. To get our minds around the truth that old solutions cannot unlock new problems. We must champion and elevate strategy to its rightful role as being by its very nature an imaginative discipline (nor merely a precursor or fluff-job for somebody else’s). We need to retire the policers and enforcers. We should ask “and what happens next?!” and seek to surprise ourselves again. We should take the mental shopping trolley to the top of the hill, set it alight (if only for dramatic effect)… and then let go. We should do so not out of self-indulgence but because as Ann Pendleton-Jullian writes:

“The imagination brings us things that are strange - that are outside our daily experiences. It is a cognitive image-making process that presents us with images which often make only intuitive sense at best. Yet they hold untold wealth”

***

Sources

Stephen T Asma, The Evolution Of Imagination, 2017

Stephen T Asma, ‘Imaginology’, aeon, 26 May 2022

David Beer, The Quirks of Digital Culture, 2019

Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman, ‘The Creativity Crisis’, Newsweek, October 7th, 2010

Finn Brunton, Spam: A Shadow History of the Internet, 2015

Kyle Chayka, How the Internet Turned Us Into Content Machines, The New Yorker, 4 June 2022

Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths, Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions, 2016

Brian Christian, The Most Human Human: What Talking With Computers Teaches Us About What It Means to Be Alive, 2021

Harry Collins, Artifictional intelligence: Against humanity’s surrender to Computers , 2014

Ben Davis, Art in the After-Culture, Capitalist Crisis and Cultural Strategy, 2022

Ben Davis, ‘Why KAWS global success may well be a symptom of a depressed culture, adrift in nostalgia and retail therapy’, art net.com, 3 March 2021

Ben Davis, 'NFT Artists Are Not Selling ‘Digital Art Objects.’ They Are Selling a Story - One That Requires Constant Retelling’, art net.com, 16 August 2022

Dionysios Demetis & Allen Lee, ‘When humans using the IT artifact becomes IT using the human artifact’, Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2017

EMSI, ‘STEM Majors Are Accelerating in Every State’, 20th March 2016

Paul Feldwick, ‘50 years using the wrong model of TV advertising’

Ed Finn, ‘Algorithms Are Redrawing the Space for Cultural Imagination’, The MIT Press Reader

Ed Finn, What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing, 2017

Mark Fisher, ’No One is Bored, Everything is Boring’, in K-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher (2004 – 2016), 2018

Adam Frank, ‘Thinking thresholds: Is science the only source of truth in the world?, Big Think, 4th February 2021

Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: A History, 2013

Mario Gabriele, ‘Endless Media’, The Generalist.com

Maxine Greene, Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, the Arts, and Social Change, 2000

Ted Gioia, ‘How short will songs get?’, The Honest Broker

Henry Giroux, ‘Authoritarian Politics in the Age of Civic Illiteracy’, CounterPunch’, 15 April 2016

Luke Greenacre, Nicole Hartnett, Rachel Kennedy, Byron Sharp, ‘Creative That Sells: How Advertising Execution Affects Sales’, Journal of Advertising · September 2015

Karen Hao, ‘We read the paper that forced Timnit Gebru out of Google. Here’s what it says’, Technologyreview.com, 12th May 2020

Holly Herndon & Mathew Dryhurst, artreview.com, 10 January 2023

John Higgs, William Blake vs The World, 2021

Ted Hughes, in Children's Literature in Education, March 1970

Alan Kirby, Digimodernism: How New Technologies Dismantle the Postmodern and Reconfigure Our Culture, 2009

Marshall McLuhan Interview from Playboy, 1969

Roger Martin, ‘Overcoming the Pervasive Analytical Blunder of Strategists’, 17th May 2021

Roger Martin, ‘Strategy is about imagination, choices and capabilities’, June 8th, 2021

Roger Martin, ‘What would have to be true? The most valuable question in strategy’, August 2022

Roger Martin, ‘Why planning over strategy?’, 29th August, 2022

Roger Martin, ‘Asking Great Strategy Questions’, 7th June, 2021

Geoff Mulgan, Another World Is Possible: How to Reignite Social and Political Imagination, 2022

Anne M. Pendleton-Julian and John Seely Brown, Design Unbound: Designing for Emergence in a white water world, Volume 1

Neil Postman, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology, 1992

Joshua Rothman, ‘Creativity Creep’, The New Yorker, 2nd September 2014

https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/greta-van-fleet-anthem-of-the-peaceful-army/

Simon Reynolds, Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to its Own Past, 2010

Derek Thompson, ‘What Moneyball for everything did to American culture’, The Atlantic, 30 October 2022

Caren Walker and Alison Gopnik, ‘Causality and imagination, The development of imagination, ed. M. Taylor, 2013

John Warner, Why They Can't Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities, 2018

Orlando Wood, Lemon: A Repair Manual to Reverse the Crisis in Creative Effectiveness, 2019

Adrian York, ‘Pop songs are getting shorter’, 16 June 2022, inews.co.uk